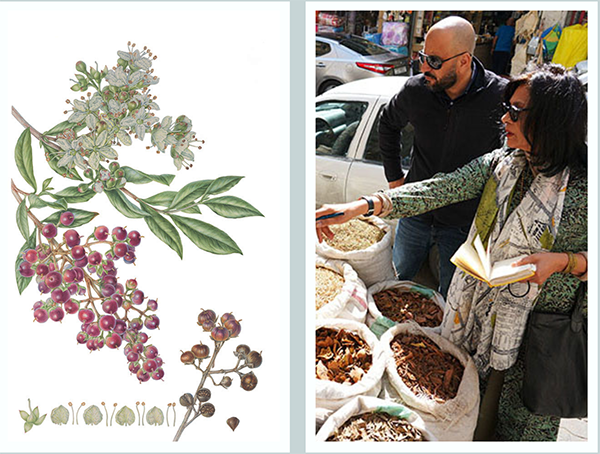

Dr Shahina Ghazanfar (NC 1978) has published Plants of the Qur’ān: history and culture. It is the first book to explore the history of the plants in the Qur’ān, from pomegranates and grapes to ginger and garlic, leading to new findings in our knowledge of the historical and cultural significance of these plants, their traditional and present uses. Each of these plants is illustrated with beautiful botanical paintings by artist Sue Wickison (her depiction of a henna fig plant is pictured above, courtesy of the artist), drawn from living specimens in the wild.

A recipient of the Phyllis and Eileen Gibbs Travelling Fellowship (22/23), Shahina is an expert on the flora and vegetation, conservation, and plants of economic importance in the Middle East. She is a senior botanist at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. The photo above, courtesy of Shahina, shows her identifying plants in a market in Amman, Jordan.

The book and illustrations are currently on display in an exhibition at Kew Gardens.

“My research starts with cuneiform sources since the history of herbal medicine is believed to have begun in classical antiquity,” she says. “Cuneiform texts on clay tablets reveal that ancient Mesopotamians knew about healthcare and used plants to cure diseases and other health conditions more than 5,000 years ago. Several plant names in Akkadian and Sumerian (the languages of ancient Mesopotamia) are identified as medicinal plants that exist (and some are still used) in present-day Iraq.

“I am particularly interested in researching plants used in diagnosis in the Greco-Arab medical system, or Unāni Ṭibb. Unāni Ṭibb, which was developed by Muslims in the Middle East and Iran, using the Hippocratic and Galenian principles of diagnosis, is still practised in several countries of the Middle East.”

Shahina conducts much of her research in person, interviewing experts in the Middle East – often older women – about their use of the plants.

“I have adopted my research method by visiting herbal shops selling traditional plant-based medicines, and conducting interviews with sellers about where the plants come from, how popular these preparations are, and what section of society purchases them,” she explains. “I have also visited and interviewed individuals (mostly elderly mothers) at their homes to learn about their knowledge of medicinal plants.

“Countries that I have visited include the Sultanate of Oman, Jordan, and Cordoba. I have studied one of the earliest collections of medicinal herbs from Iraq, Syria, and Palestine made by Leonhard Rauwolff in 1574–75 and a collection from Iraq made by Aucher-Éloy in the early 19th century.”

Shahina is now working on a new book on medicinal plants. “I have started writing my findings in book form to describe 200 plants as they are known to be used now and have been in ancient times,” she says.

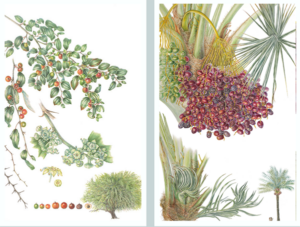

She is also co-editor of Flora of Tropical East Africa, author of The Flora of Oman and author and editor of Flora of Iraq. (Paintings above by Sue Wickison show a Ziziphus fig – left – and a date palm).

Illustrations from Plants of the Qur’ān: History and Culture. Kew Publishing. © Sue Wickison; Reproduced with permission.

- Date Palm (Phoenix dactylifera) is mentioned several times in the Quran; besides the date (fruit), the tree and fronds are used for roof beams, and fences, to make rope for baskets, mats, and screens

- Henna (Lawsonia inermis), the leaves are made into a paste with water and used to dye hair, hands, and feet in intricate patterns for Islamic celebrations such as Eid al Fitr and Eid al Adha, marriages, and birthdays.

- Sidr (Ziziphus spina-christi), powdered leaves used as soap and shampoo.